- Agenda appuntamenti e news

- Biografia cronologica

- Libri

- Dicono di me (rassegna stampa)

- Recensioni

- Spettacoli teatrali

- Books

- Video

- Storytelling and Theater Shows

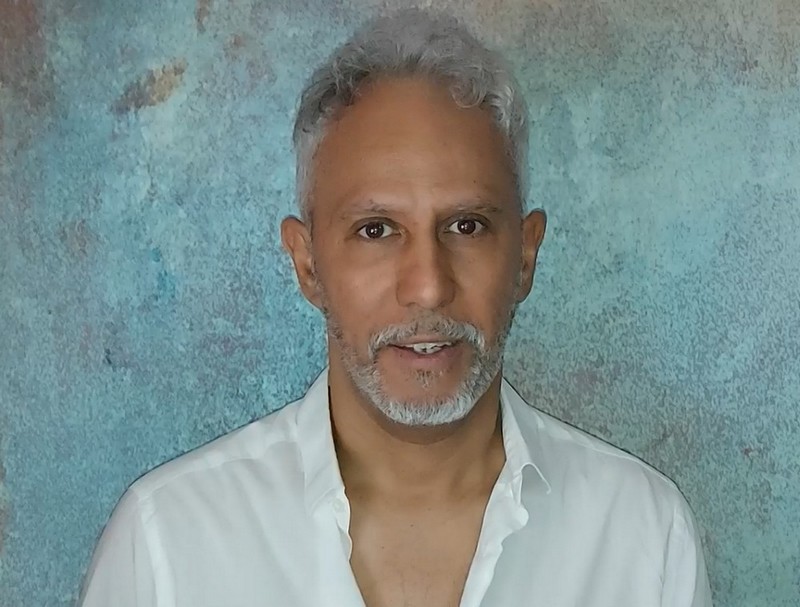

- Alessandro Ghebreigziabiher foto di scena

- Canzoni dal vivo (live songs)

- Alessandro Ghebreigziabiher stage photos

- Foto con Cecilia Moreschi

- Español

- Français

- Contatti

- Ottieni link

- X

- Altre app

If you prefer a more formal and traditional biography, click here.

I was born in Naples on 20 May 1968, between two

Souths.My father Araya’s South, who arrived in Italy from Africa — Eritrea, around the middle of the last century, and my mother Paola’s one, a daughter of Naples.

Two different kinds of immigrants, if you like, both driven less by desire than by necessity to seek something better north of their respective homelands.

Thus, the South of the world and the South of Italy metthrough my courageous parents in late-1960s Naples, giving life to a pioneering “mixed couple” in a country far from ready to accept them — and even now, more than sixty years on, I am not sure things have changed as much as I would wish.

So, when I was still very young, I followed my parents to Rome, which became my city of yesterday, today, and very likely of every tomorrow to come.

I did not have an easy childhood, nor was adolescence a smooth ride, for family, personal and economic reasons. But I give you my word: my parents’ ethnic and cultural differences were never a problem. If anything, they were a resource that helped me emerge from a truly complicated situation.

That does not mean it was easy to be born in Italy at the end of the 1960s with my skin and my origins. Suffice it to say that I was the only dark-skinned student in every school I attended from nursery right through to university and beyond. The same was true in the neighbourhood and playgrounds — and above all at the seaside, where that overrated peculiarity becomes all the more visible.

All this is to say that I know what racism is; I have lived it since childhood and I still live it on my own skin today, and it is only for this reason that I sometimes speak of it, convinced that it gives me a certain authority to do so. But even better than racism I know solitude, and the desperate need to find somewhere — anywhere, an anchor to survive suffering.

Even so, I would like to stress that despite everything, I still consider myself extremely fortunate, and I have always faced things with a smile on my face. Almost every obstacle found its remedy within me. Life has taught me that out there are billions of people who have not managed to overcome theirs, often because someone else has done everything possible to make the task difficult, or even impossible.

I believe it is for all these reasons that from a very young age I fell in love with stories. I’ve read an endless number of them and continue to read voraciously. For the same reason I write and tell them. Once, I did so without even realising it. Later I became more conscious of it, and that awareness brought me great peace.

It is hard to believe that writing might genuinely be one’s path. At the end of the 1980s, during my final exams, I probably wrote the best essay of my entire school career. In the previous six years — I publicly confess I was held back in the third year for two subjects, although at that tragic time school was the least of my worries, I had barely managed to scrape a pass in Italian essays. Only at the final exam did I understand why: the problem had always been the prompts.

During the exam, I picked up my pen and wrote about the years spent at Keplero Secondary School in Rome. I still remember the examiner’s words — the Italian teacher. She told me that although I had gone completely off topic, in her view my text was excellent and ought to be published. Then she asked what I intended to do after school.

As it happened, since childhood I had shown an impressive ease with mathematics. Nothing extraordinary — just an innate ability, which I later lost, to carry out mental calculations, even with three-digit numbers, in a few seconds. And so, like many of my generation, with my head full of nonsense about the dangers of being misled by one’s dreams, I replied that I would enrol in engineering because it would make it easier to find a job.

“What a pity,” the examiner observed. “You’re a young man with a gift for the writing…”

I lasted a whole two years in engineering, even managing to pass nearly all the first-year exams, but then something cracked inside me. I began to feel a deafening urgency which I eventually listened to and followed. Meanwhile, my passion for theatre and social work had exploded. The marriage of these two led me, in 1993, to the San Carlo recovery community for former drug addicts at the Italian Centre for Solidarity (CE.I.S.), where I served as a conscientious objector. I want to stress that my choice between civil and military service was, before anything else, logical — realistic: I genuinely wanted to give a year to my country. Everyone I knew who had done military service had told me they had spent a year doing nothing of importance, and for me time has always had great significance, for obvious reasons.

During that year in the community I gave everything I had, yet even now I feel it was very little compared to what I learned — about myself and, above all, about others.

Meanwhile, I changed degree courses and transferred my meagre handful of credits to Computer Science. The real reason? It was still a practical degree with excellent job prospects, which somewhat softened my father’s disappointment, but it was also less demanding than engineering and would therefore give me more time for theatre and social work, as well as music and — more than anything, people.

Once again, then, I found myself between two different worlds: still between two Souths, but also between the coldness of computers and the unpredictability of my most unrestrained passions.

The decisive year was 1998, the year of my graduation. Yes — a young man with such a complicated and troubled history managed to earn that long-awaited piece of paper, as it used to be called in Italy.

Nonetheless, it’s time for confessions, and I address the professor who gave me top marks in Analysis II. Professor, do you remember me? Do you recall how, at the oral exam, you asked your first question and I remained silent? Do you remember how, convinced I was a foreigner, you asked whether I had problems with the Italian language — and I said yes? Forgive me: I lied shamelessly…

A few months before my final thesis defence, I approached the head of the community and officially proposed myself as a “theatre facilitator for distress” at the CE.I.S. The management responded by entrusting me with three groups, each with participants from different recovery programmes. After the summer I also began working as an IT teacher.

Once again, I was in-between — this time between ordinary lessons at a school and special ones in care settings.

In that same year I wrote Sunset, the theatrical monologue that in 2002 became a children’s book published by Lapis Edizioni. A simple metaphor: sunset — between day and night, between light and darkness, a mask inevitably caught between two worlds.

Two years before the publication of what became my first book, in 2000, I understood that outside theatre, masks are the worst obstacle for anyone wishing to tell something rooted in everyday reality, or even simply moving in its direction. So I took that long-awaited piece of paper and placed it in a metaphorical drawer to dedicate myself solely to work as a theatre facilitator — of distress or otherwise.

It was a difficult choice, one I have often questioned over the years, only to reaffirm it with renewed conviction.

In those days I chose to earn less and to have less financial security, but the fulfilment I found in doing a job whose value is, above everything, human, is priceless.

In 2005, another deeply significant year shaped my journey.

In May, the CE.I.S. programme in which I’d worked for the preceding five years suddenly had its funding cut, and I found myself, at the venerable age of 37, unemployed with a one-year-old child — though shared with a wonderful partner, Cecilia Moreschi.

As if that weren’t enough, in August I learned that my father had lung cancer and that doctors had given him at most six months to live.

Part of me was shattered. As a writer I had many manuscripts and only one book published. Theatre brought in little money as always, and as a social-care professional I held no formal qualification — no degree as an educator or psychologist. Plenty of experience and training in the field, but no coherent piece of paper.

Certainly, you might say, I still had a degree in computer science. That year I sent out thousands of CVs, but with no luck. So I convinced myself that I had no choice but the one I had already made.

That summer I drafted the idea for the Intercultural Laboratory of Theatrical Storytelling — later simply the Storytelling Theatre Laboratory — The Gift of Diversity, which debuted in November of the same year, followed by a namesake festival that began in 2007. At the same time, the CE.I.S. offered me at least one theatre group of patients. Better than nothing, right?

At the start of 2006, one of the two Souths mentioned above left us. Araya — from Africa to Europe, from Eritrea to Italy, from Naples to Rome, Darkness, the father of Sunset, was buried in the capital. From that day on, the few good things I manage to do, I know I do also for him.

In 2017 my mother Paola also passed away. Light, the Neapolitan woman who left the South of our country with the desire to illuminate her own life and the real darkness of the man she loved. Their life together was not easy, partly because of psychological issues and addiction, whose consequences inevitably fell upon their children — but love was never lacking, and in the end that is what matters.

After Sunset came many more books, theatrical storytelling performances, events and festivals, and above all encounters with special and incredibly fascinating people — as well as much work in places where people seek help and listening in the midst of their suffering, demonstrating extraordinary strength.

For more than thirty years now, alongside my commitment to writing and theatre, I have devoted part of my working life to clinical and therapeutic settings, between communities and mental-health centres. In particular, since 2010 I have run theatre and creative-writing workshops at a day centre for adolescents with psychiatric difficulties called Navigating the Borders (Navigando i confini), which grants me the daily privilege of discovering — and rediscovering — how rich in hidden and potentially special talents young people are, despite the tragic nature of their family situations. Or perhaps precisely because of it.

What can I say? Despite everything, I feel infinitely grateful for the life I’ve lived so far.

Nonetheless, the best things I have are my wife and our two children.

My greatest hope, still today, is to help them achieve their dreams.

- Ottieni link

- X

- Altre app